|

"Wer nicht liebt Wein, Weiber und Gesang, Der bleibt ein Narr sein Lebelang."

—Martin Luther, quoted in "Wandsbecker Boten" newspaper in 1775: "Who doesn't love wine, women, and song remains a fool his whole life long."

|

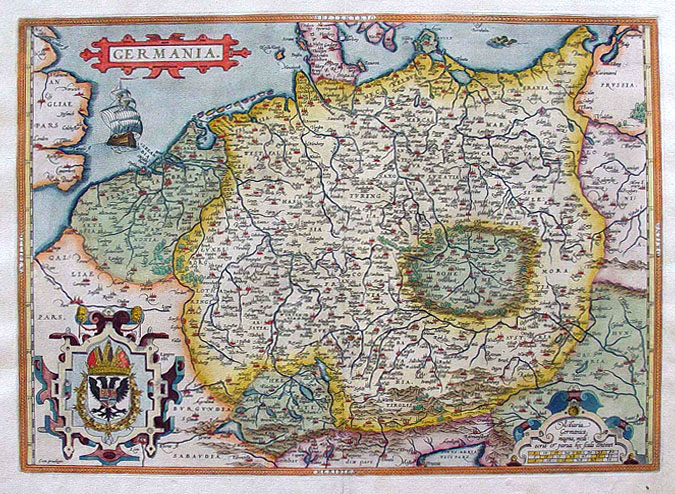

The Counts of Hessen descended from the Counts of Thüringen—and both Hessen and Thüringen use a striped lion in their arms (an early example is shown, above).

Hessen was split into several states 500 years ago, when the Hauß surname was first recorded, but an important area, where the family had a line of aldermen, was Hessen-Marburg, a "Landgraviate" (i.e. a principality directly under the Holy Roman Emperor) that existed independently between 1485 - 1500 and again between 1567 - 1605. It was comprised of the city of Marburg and the surrounding territories (what is today called "Oberhessen," or "Upper Hessen").

|

Detail from an ancient German map showing Cherusci, Chamavi and other tribes. Published by Taylor, Walton and Moberly in 1851. |

During the period of the Frankish Empire, the territory was divided into several Gaue (districts)—called Saxon Hessengau, Frankish Hessengau, Buchonia, and Oberlahngau. The Gaue were ruled over by counts (Grafen).

The Frankish king, Clovis, was converted to Christianity in the 4th century, and he was responsible for the conversion of his nation and the Saxon tribes. The Chatti, now Christians, reemerged under the name "Hessens," and their land eventually formed the state of Hessen. But despite the religious conversion, their warring nature remained.

In the tenth and eleventh centuries a new line of nobility emerged, called the Gisos, or the Counts of Gudensberg. The daughter of the last Giso married Count Louis I of Thüringia, became the landgrave in 1130. Hessen and Thüringia were then united until the War of the Thüringian Succession (1247-64). After the fighting was over, Hessen had gained its independence. It became an earldom within the Holy Roman Empire. The new ruler, Henry I the Child, founded the Brabant dynasty of Hessen. He was raised to the rank of a prince of the Holy Roman Empire in 1292.

By the end of the fifteenth century, the Landgrafschaft of Hessen was the greatest and strongest power of central western Germany. Over the next two centuries the landgraves expanded their territory and often clashed with the neighboring archbishop-electors of Mainz.

Then in 1458, Hessen expanded after a division of territory within the Holy Roman Empire. The new ruler, Ludwig the Peaceful, created a sub-landgraviate for his younger brother, Henry. Henry was based at Hessen-Marburg, where our Hauß family would first be recorded.

Electores

septem sacri imperii spirituales - Imperator gloriosus - Sexta etas mu(n)di seculares

- Schedel H., 1493. This woodcut shows the emperor and electors of the Holy Roman

Empire with twenty four German noblemen presenting their coats of arms.

Electores

septem sacri imperii spirituales - Imperator gloriosus - Sexta etas mu(n)di seculares

- Schedel H., 1493. This woodcut shows the emperor and electors of the Holy Roman

Empire with twenty four German noblemen presenting their coats of arms. |

Landgraf von Hessen |

Philip the Magnanimous (at right), the landgrave from 1509 to 1567, was born at Marburg on the 13th of November 1504, and became landgrave after his father's death in 1509. The epithet "magnanimous" that has been handed down through the centuries is probably a mistake: The translation of his title, der Großmütige, does mean "magnanimous" in modern German, but in Renaissance German, when he lived, it appears to have meant "haughty." And that is a much better description of this man's reign.

Having been declared "of age" in 1518, he was married in 1523 to Christina, daughter of George, duke of Saxony. Philip was a cultured intellectual, who created a University in Marburg (which eventually claimed the Brothers Grimm in the faculty). But he was also a fiery, controversial leader who spent most of his reigning years at war. In 1525 he took a leading part against the rebellion of the peasants in north Germany, crushing them at Frankenhausen.

After the battle, Philip I adopted the reformed faith (a denomination that the Hauß family would follow for the next 200 years), and he is remembered today as the German Prince (Fürst) who saved Protestantism in Germany, forming the League of Torgau in 1526.

But we need to ask an important question: What was the reason for Philip's conversion to the reformed faith? Well, it wasn't about church practices as much as it was about a girl... or two. Basically, we have Protestantism today so that Philip could practice bigamy, with the help of an Augustinian monk and theology professor named Martin Luther.

The first meeting of Philip with Luther was in 1521 at the Diet of Worms, but at that time he had little interest in the religious theories of the famous reformer. It was only after Philip's marriage with Christina, the daughter of George of Saxony, early in 1524, that he began to take an active part in forwarding the cause of the Reformation. Within a few weeks after marrying the unattractive and sickly Christina, who was also alleged to be an alcoholic, Philip had committed adultery.

|

|

In 1526, Philip began to consider marrying a second wife. He was influenced by the case of Henry VIII, in which the Reformer Melanchthon had proposed that the king could take a second wife instead of divorcing the first one. Then there were Luther's sermons on Genesis, as well as historical precedents in which God had not punished people in the New Testament who did the same thing, and instead held them up as models of faith. Philip wrote Luther for his opinion on bigamy, citing the polygamy of the patriarchs; but Luther replied that it was not enough for a Christian to consider the acts of the patriarchs, but that brides and groom, like the patriarchs, must have special divine sanction. Since, however, such sanction was lacking in Philip's case, Luther advised against another marriage. Despite this discouragement, Philip continued his affairs and polygamous schemes, which for years kept him from receiving communion.

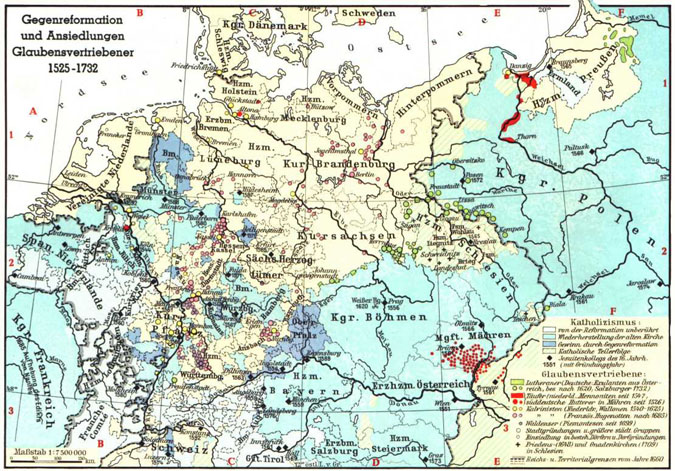

The

Ecclesiastical Counter-Reformation, between 1525 - 1732 (click

to enlarge).

The

Ecclesiastical Counter-Reformation, between 1525 - 1732 (click

to enlarge). |

|

Unfortunately, Philip's impulsiveness proved his undoing: While recuperating from an illness due to "excesses," the idea of bigamy became Philip's main obsession. He decided to marry the daughter of one of his sister's ladies-in-waiting, named Margarethe von der Saale. But Margarethe was unwilling to take the step unless they had the approval of the theologians.

Philip finally won the grudging approval of a second marriage as a concept, at least, from Luther and Melanchthon, without either of them knowing that the next wife had already been chosen. Melanchthon was then summoned to Rotenburg-on-the-Fulda, where on March 4th, 1540, Philip and Margarethe were wed.

|

Philip was bitterly disgusted by the criticism, and worse yet, feared that a law which he himself had enacted against adultery might be applied to his own case. Philip decide that he had to make his peace with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and obtain a pardon, but on terms which would not involve desertion of the Protestant cause. He offered to observe neutrality regarding the imperial acquisition of the duchy of Cleves and to prevent a French alliance, on condition that the emperor would pardon him for all his opposition and violation of the imperial laws (without direct mention of his bigamy, of course). But on July 20, 1546, an imperial ban was declared against Philip as a perjured rebel and traitor. The result was the Teutsche Krieg, or Schmalkaldic War.

|

|

The

defeat at Mühlberg and the capture of Philip's ally, the Elector John Frederick,

marked the fall of the Schmalkald League. In despair Philip, who had been negotiating

with the emperor for some time, agreed to throw himself on his mercy, on condition

that his territorial rights should not be impaired and that he himself should

not be imprisoned. Not surprisingly, these terms were disregarded, however, and

on June 23, 1547, both Philip and John Frederick were taken to south Germany and

held as captives.

The jailing of Philip brought the Church

in Hessen into crisis. It had been organized carefully by Philip and thoroughly

reformed. But now an "Interim" was introduced, sanctioning Roman Catholic

practices and usages. Philip himself wrote from prison to personally sanction

the Interim (as his life depended upon it). The Hessian clergy, however, opposed

the introduction of the Interim and the government at Cassel refused to obey the

landgrave's commands. Fearing more punishment from his Catholic captors, Philip

then made an unsuccessful attempt to escape. He was finally released in 1552,

following the Treaty of Passau, in which Holy Roman Emperor Charles V guaranteed

Lutheran religious freedoms and ended his quest for European religious unity.

A greatly deflated Philip then returned to Hessen. The terms

of Philip's release led to the collapse of his position as the leader of the Protestant

party. He had become an object of suspicion. The militant arm of the Protestant

movement was handed to French theologian John

Calvin. But although Philip was less active, the landgrave did not cease to

work behind the scenes on behalf of the Protestants.

Ultimately,

Philip failed in his attempts to reconcile Swiss and Lutheran doctrine, but his

efforts to form a union of the Protestants proved fruitless (unlike his second

marriage, which yielded seven sons and one daughter).

Philip died at Cassel on the 31st of March in 1567. He had four sons and five daughters by wife #1, Christina, and according to his directions the landgraviate was partitioned at his death between their sons. His sons by wife #2 were named counts of Dietz. Hessen was broken up into much smaller states: His eldest son, Wilhelm IV, inherited the northern portion (Hessen-Kassel). George I, the youngest son, received the upper county of Katzenelnbogen, and became the founder of the Hesse-Darmstadt line. Two other sons received Hessen-Rheinfels, and the previously-existing Hessen-Marburg.

|

|

Religious tensions were high throughout the second half of the 16th Century. The Catholics of eastern Europe (Poland and Austrian Habsburgs) were trying to restore the power of Catholicism. The area that the Hauss' resided was mainly Lutheran. When Count Ludwig of Hessen-Marburg died childless in 1604, a conflict arose between his nephews, Wilhelm of Hessen-Kassel and George of Hessen-Darmstadt, over who would get his territory. He bequeathed equal shares of his territory to the lines of Hesse-Kassel (Marburg) and Hesse-Darmstadt (Gießen, Nidda), yet under the condition that both territories should remain Lutheran (Hesse-Kassel was Calvinist). But the two sides would fight over the land for decades.

This controversy broke into violence in the German town of Donauw(?) in 1606. The Lutheran majority barred the Catholic residents of the town from holding a procession, causing a riot to break out. This prompted Duke Maximilian of Bavaria (1573-1651) to intervene on behalf of the Catholics.

After the ensuing violence ceased, the Calvinists in Germany (who were still in their infancy and quite a minority) felt the most threatened, so they banded together in the League of Evangelical Union, created in 1608 under the leadership of the Elector Palatine, Frederick IV (5 March 1574 - 19 Sept. 1610). He was also called Frederick the Righteous, or Friedrich

Der Aufrichtige. The only surviving son of the elector Louis VI, who died

in October 1583, Frederick began his rule at the age of ten.

An

ardent Calvinist, Frederick IV took over the mantle of the Protestant political

leader from Philip I of Hessen, and continued the Reformist policies of hostility

toward the Catholic Church. This provoked Catholics to band together in the Catholic

League (created in 1609) under the leadership of Duke Maximilian.

Meanwhile,

the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, Matthias, died without a biological

heir in 1617, but had named his cousin Ferdinand of Styria as the next ruler.

Ferdinand was a staunch Catholic who had been educated by the Jesuits and who

wanted to restore Catholicism. He was therefore unpopular in mainly Calvinist

Bohemia. Since the King of Bohemia was an elected office, the Bohemians chose

the heir of Frederick IV, named Frederick V, as elector of the Palatinate. Frederick

V began his reign over the Palatinate in 1610, and so began a religious war with

it. Here is a brief overview of that war, but you won't understand it any better

than the people who had to fight in it:

THE THIRTY YEARS' WAR, 1618 - 1648.

NOTES

¹—The town is situated in Lahn-Dill-Kreis, Giesharpen, Hessen, Germany, its geographical coordinates are 50° 35' 0" North, 8° 28' 0" East and its original name (with diacritics) is Klein Altenstädten (Satellite image: http://www.maplandia.com/germany/hessen/giesharpen/lahn-dill-kreis/klein-altenstadten/). Wetzlar and the Duchy of Solm are also in the German State of Hessen. In 1977 Wetzlar was merged with Gießen to form the new city Lahn, however this attempt to reorganize the administration was very unpopular and was reverted in 1979. Heavy American bombing destroyed about 75% of Gießen in 1944, including most of the city's historic buildings.

²—The

Reichskammergericht was the highest judicial institution in the Holy Roman Empire,

founded in 1495 by the Reichstag in Worms. All proceedings in the Holy Roman empire

could be brought to the Reichskammergericht, except if the ruler of the territory

had a so-called privilegium de non appellando, in which the highest judicial institution

was founded by the ruler of that territory. The Reichskammergericht was infamous

for the long time it took to reach a conviction. Some proceedings, especially

in law suits between territories belonging to the Holy Roman Empire, took several

hundred years, some of them were not brought to an end by the time it was dissolved

in 1806 after the downfall of the Holy Roman Empire.

LITERARY

SOURCES FOR THIS PAGE: